I posted a photograph on social media last night, showing the musicians starting to take their seats on stage at the Lowry’s Lyric theatre. You can also make out how thinly populated the auditorium is. “Sparse,” a friend of mine commented. Indeed so, but, sad though this is, it is less sad than dark houses. There are not many of us allowed in, but we are glad to be here – even with a 30 minute wait before the overture.

Fidelio is Beethoven’s only opera (he couldn’t get comfortable with the art form). It’s remarkable for several reasons besides this uniqueness. It has a celebrated chorus about the joys of freedom (bound to be poignant for tonight’s audience) and is a cautionary tale of how personal animosities can hold sway in times of political upheaval. Perhaps most strikingly of all, it features a genuinely active female protagonist.

Image credit: Richard H Smith

Working as assistant warden in the state prison, Fidelio – a young man, sufficiently comely to have inadvertently won the heart of Marzelline, daughter of Rocco, the head warden – has a jealous rival, Jaquino. To complicate matters further, Fidelio is really Leonore, brave and faithful wife of Florestan – currently being starved in the dungeon, more for daring to cross the governor, Don Pizarro, than for his political beliefs.

News arrives of an imminent visit by the Minister, so Pizarro resolves to bring a swift end to his vulnerable enemy. When Fidelio is enlisted as an accomplice, Leonore vows to rescue her husband, or die in the attempt.

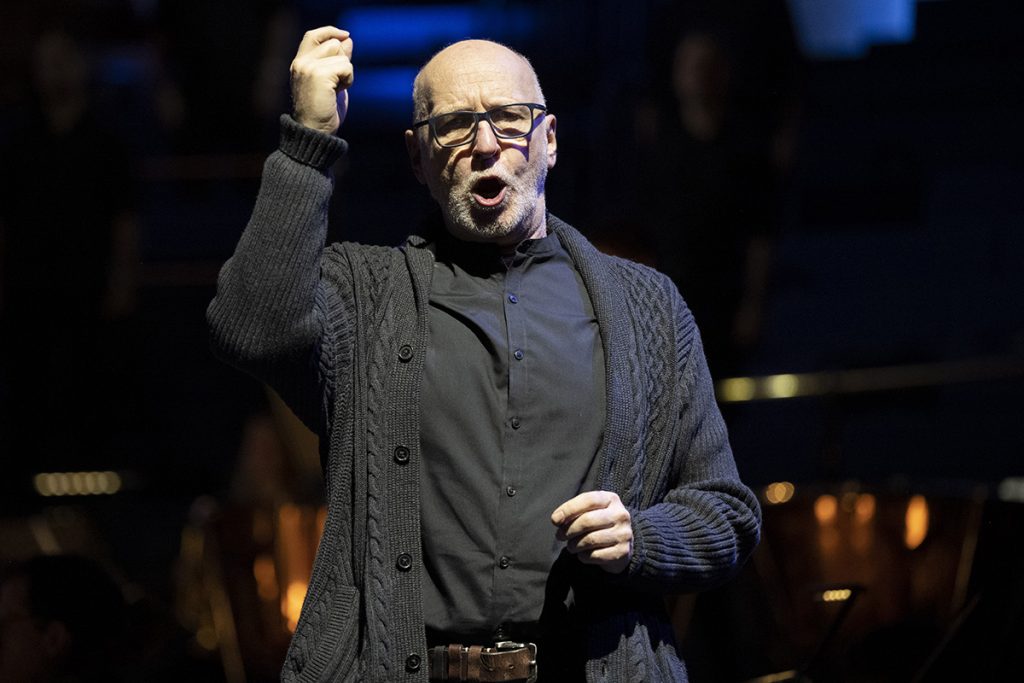

This concert production (i.e. no sets or action) makes the nifty decision to present the tale as a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. As convenor, Matthew Still brings the necessary gravitas and a crystal clarity of voice to relate the tale and help us make sense of matters in the absence of full dramatisation. (Still also gives fine singing voice to the Minister).

The device works all the better in making us focus on the music (ON’s orchestra conducted with seamless dynamism by Paul Daniel) and the voices.

Strong enough in solo sections, it is nevertheless in harmony and counter that the cast excels. The Act One quartet, “Mir ist so wunderbar,” is heart-meltingly warm, and no one does a rousing choral finale like Beethoven.

Image credit: Richard H Smith

The score for the title role has some extremely demanding intervals (mainly high to low) but Rachel Nicholls handles them while managing the blend of boyish womanly required. Despite being (of necessity) rooted to the spot, we believe this Leonore is willing to die for her husband.

The sustained and haunting anguish of Florestan’s opening note is, in itself, enough to justify Toby Spence’s name on the team sheet – a chilling opening to Act Two.

It feels like old times when Robert Hayward gets a little booing (for all the right reasons) after his stint as the malicious Don Pizarro. We can but hope that Marzelline (a warm and witty performance by Fflur Wyn) will eventually yield to the entreaties of Paquino (Oliver Johnston gives us a needy suitor with no real harm in him).

My favourite voice of the night belongs to Brindley Sherratt’s Rocco. Sherratt has his woofers and tweeters perfectly balanced. His every contribution adds depth and dimension. Bravo.

The Opera North chorus, under Oliver Rundell, is always a pleasure.

“Let’s celebrate all the wonderful women,” as Sonnleithner’s libretto enjoins us. The men here are none too shabby, either.

Welcome back, ON. Here’s to a time when we can pack the house to salute you.