Opera North, in collaboration with Phoenix Dance, bring us a triple bill: two parts Bernstein with a new piece (“Halfway and Beyond”) based on a contemporary poem, sandwiched between.

The evening opens with a revival of Matthew Eberhardt’s 2017 production of Bernstein’s one act satirical opera, Trouble In Tahiti. The show closes with a version of his West Side Story Symphonic Dances, choreographed and (apparently) transposed to apartheid South Africa by Phoenix’s artistic director, Dane Hurst.

1952, the USA. Sam and Dinah are a married couple with a young son, Junior, living in white picket fence suburbia of a kind (as the libretto reminds us) to be found all across the country. Sam (Quirijn de Lang, looking every inch the young exec, but sometimes struggling to deliver at the lower end of the baritone scale) is married to Dinah (Sandra Piques Eddy, increasingly comfortable as the unfulfilled post-war wife, in the jazzier elements of the score).

Whilst at work Sam is popular and a winner, (‘golden-hearted Sam’ – despite perhaps once behaving inappropriately towards his secretary, Miss Brown), at home all is friction and disillusionment. Dinah tells her therapist about a dream in which a young man (aged 17, like her dream self) promises to lead her away from a garden (with ‘every kind of weed’) to something better, but that he vanishes in smoke, leaving her surrounded by nightmarish visions.

Both Sam and Dinah acknowledge that they need to talk, but when the opportunity arises with a chance meeting in the park, each chooses to sing about, rather than to, the other.

The couple’s lives are presented with occasional backing from a radio show trio, the libretto constantly reminding them that acquisition is the road to fulfilment. Three years earlier, Bernstein had written the score for the popular film musical, On the Town, and here the notation echoes the music from that phrase whenever the trio repeat the words, “in suburbia.” The irony would surely not have been lost on audiences of the time.

Having, once more, shown himself a winner (this time by carrying off the handball trophy at the gym) Sam acknowledges there is always a price to be paid – a price which for him begins as he steps through his own front door.

Dinah has made a real effort, getting dolled-up and preparing a candle-lit dinner, but to no avail. Sam insists they must talk, but then loses his nerve, instead inviting his wife to go to see a new movie, “something about Tahiti.” She agrees, even though we know she saw it (and hated it) that very afternoon.

Pointedly and poignantly, the cause of their breakfast row – about going to watch their son appear in the school play – is not even brought up. While Sam’s self-preoccupation took him to the handball final, Dinah’s led her to a matinee at the movies. Neither witnessed Junior’s debut. The boy watches on, forlorn, forgotten, as his parents slide towards a fake, silver screen ending; neither giving him a backward glance or guilty afterthought.

Bernstein is no Stephen Sondheim: his libretto is somewhat on-the-nose. The themes, however – the hollow promises of consumerism, the deceitful allure of romantic fantasy, the marginalisation of children – have a modern ring.

Charles Edwards’s set design offers all the studiedly patchy artifice of a soap opera – here’s a designer with vision and a mastery of technique.

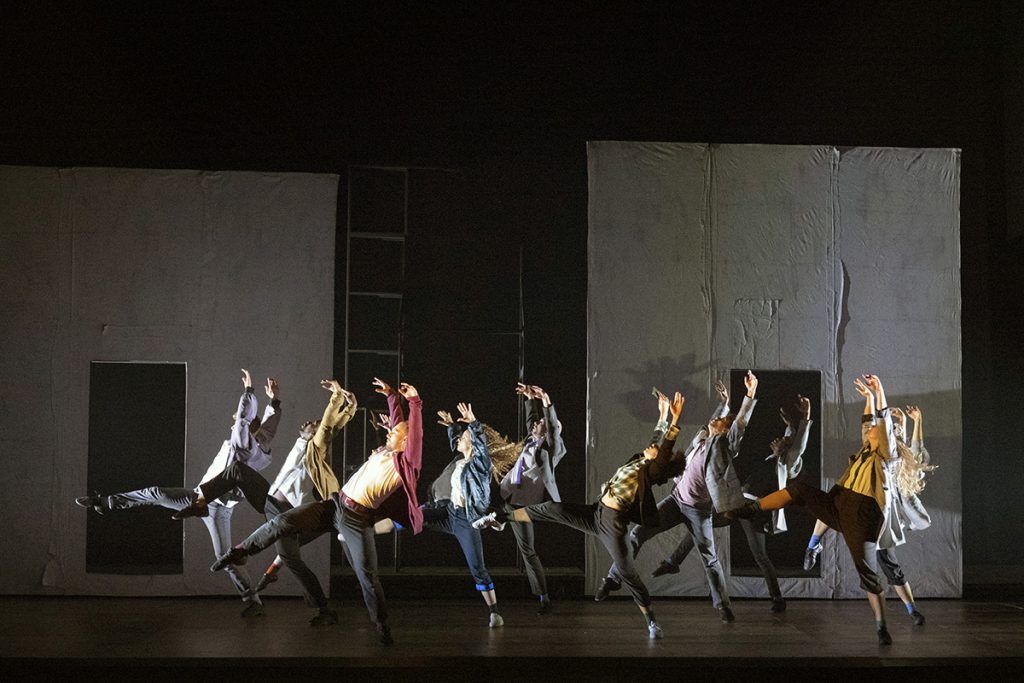

In their second collaboration with Opera North, Phoenix Dance once more decide to square up to iconic choreography. As with The Rite of Spring (choreographed in their reworking by Saintus), Dane Hurst’s resetting makes for a tame comparison with the original.

There should be no sacred cows in art (Seeta Patel has recently choreographed a gripping bharatanatyam piece to Stravinsky’s music). But where both Nijinsky and Robbins punched us in the stomach and slapped our faces (and, in Robbins’s case, occasionally writhed and squirmed in our laps), Phoenix’s Hurst gives us a genteel “proletarian” uprising – it’s as if we’re watching rough boys and girls portrayed through the cosseted eyes, minds and bodies of kids from some right-on private school.

Where Nijinsky and Robbins understood they were dealing with matters of life and death, dance moves in the savage strokes and searing colours of Van Gogh, Picasso, Basquiat, Hurst offers a pleasant watercolour. There is no compelling sense of racial tension and oppression (despite the claim to have reimagined the work for a South African setting). When one of the dancers falls “dead” it might as well be from the shock of having his allowance stopped; he surely doesn’t feel like the victim of a murderous apartheid state.

Having followed Phoenix Dance for almost thirty years, and long thought them a fine and necessary company, it breaks my heart to say it, but I’m no longer sure I would buy a ticket to see them.

Between these two pieces is “Halfway and Beyond,” set around a poem written and recited by Khadijah Ibrahiim. The words work well with the sparse set (Charles Edwards and Hyro) and bleak lighting (Kieron Johnson), though Ibrahiim’s text is so dense that it fights for attention with Dane Hurst’s choreography (the former more arresting than the latter). It’s an interesting experiment, and one worth pursuing, though I might suggest that the words, just like music will need to be written with dancers in mind.

The dancers worked hard (as dancers always do) and earned a nice ovation. Martin Pickard conducted ON’s orchestra with such great verve that I missed Jerome Robbins all the more.

Opera North – Trouble in Tahiti / Symphonic Dances is at The Lowry, Salford Quays from 11 – 13 November 2021