Mrs Lowry and Son tells the story of Salford artist, L.S. Lowry’s relationship with his controlling mother, Elizabeth. Carmel Thomason meets its stars, Timothy Spall and Vanessa Redgrave.

In the Lowry galleries a short film, made in 1957, runs on a loop about the artist’s life in Pendlebury, Salford. While preparing for his role as L.S. Lowry in Mrs Lowry and Son, Timothy Spall watched that same film six or seven times a day to capture the humanity and physicality of Laurie Lowry, the man behind the paintings. “You don’t see him speaking, you see him wandering around, it’s a postage stamp portrait of how he did it, his influences and so on,” Spall explains. “Films about artists can be very dull particularly if they reinforce our ideas of a romantic character with flowing hair. There was this clumsiness about Lowry and this wonderful, spritely ungainly thing. There’s this – for want of a better word – ordinariness.

“I’ve found out that all artists are like any human being – they have the same worries however much driven by their desire to record what they see. And often, contrary to popular opinion or romantic opinion, artists are not romantic, dashing, rather lovely characters. They are often surprisingly very ordinary and unpalatable in some cases. But they use their great talent as artists to communicate their feelings and often they can teach us things about us and our environment”.

The unpalatable part of Lowry’s history presented in the film, is the psychological abuse he suffered at the hands of his mother, Elizabeth, whom he cared for in their two-up, two-down terraced home until she died in 1939, when Lowry was 52-years-old.

The film is adapted from a Radio 4 and later a stage play of the same name, also by writer Martyn Hesford. Set in 1934, between the hardship of two World Wars, it is more or less a two-hander which focuses on the complicated and claustrophobic relationship between Lowry and his hyper-critical mother, played by Vanessa Redgrave.

Although bed-ridden, Elizabeth manages to control her bachelor son through constant checks on the minutiae of his life, such as clocking the exact time he arrives home, demanding his coat, damp from a Manchester downpour, doesn’t drip water on the floor and quizzing him about washing his hands. At times appearing vulnerable, Elizabeth pleads for her son never to leave her in one sentence, yet as Vanessa Redgrave reminds us there is nothing redeeming in her character, for her next breath is used as a spike: “After all, what woman would have you?”

We know little about Elizabeth’s life aside from that which involved her son. The film leaves us little the wiser, but as Ms Redgrave remarks, that keeps our focus on the artist. “I don’t expect them (the audience) to feel anything for her because you don’t learn quite enough about her,” she says. “When you see the film, you learn more about who she was, but especially about who her son was.

“What makes me want to watch the film is to see this man, a human being, living in a crucible of suffering and simultaneously his spirit is connecting through the paint to every human being that he sees. Great art – where does it come from? That’s what makes one want to see this story.”

Although heavily influenced by his mother, Lowry’s talent was rarely encouraged by her. In the film we see her reading out bad newspaper reviews calling his work an ‘insult to the people of Lancashire’ as if he had painted in order to embarrass her. In her view his paintings are ‘squalid industrial scenes that nobody wants to buy’ and he is a disappointment to her snobbish desire for social climbing, just like his father was before him.

“He does suffer but also it was the only life he knew,” says Spall. “It was difficult. We see her disapproving, but he grew up enthralled to her every need. There was no other, as far as we know, no other human being infiltrated into that intimacy, because he was conditioned to be like that. He got his joy, his pleasure and his satisfaction all from her. He had friends as we all know, individual friends, he never mixed them.

“As far as he did take this abuse, the painting also grows out of that abuse, but it also grows out of a stubbornness which he inherited from her. It’s also private, it’s not revenge but like Vanessa said – the spirit, the compulsion. He knew that he was upsetting her, and I think that’s in the work.

“It’s a bit like saying if Dickens hadn’t grown up with an extraordinary father who was a failure and ended up having to go and work in a bottling factory at the age of 12 or 13, coming from a middle class background would he be Charles Dickens? Probably not, because he was forced to live in an environment that he wouldn’t have done before and so he understood it. You can’t take the man out of the circumstance”.

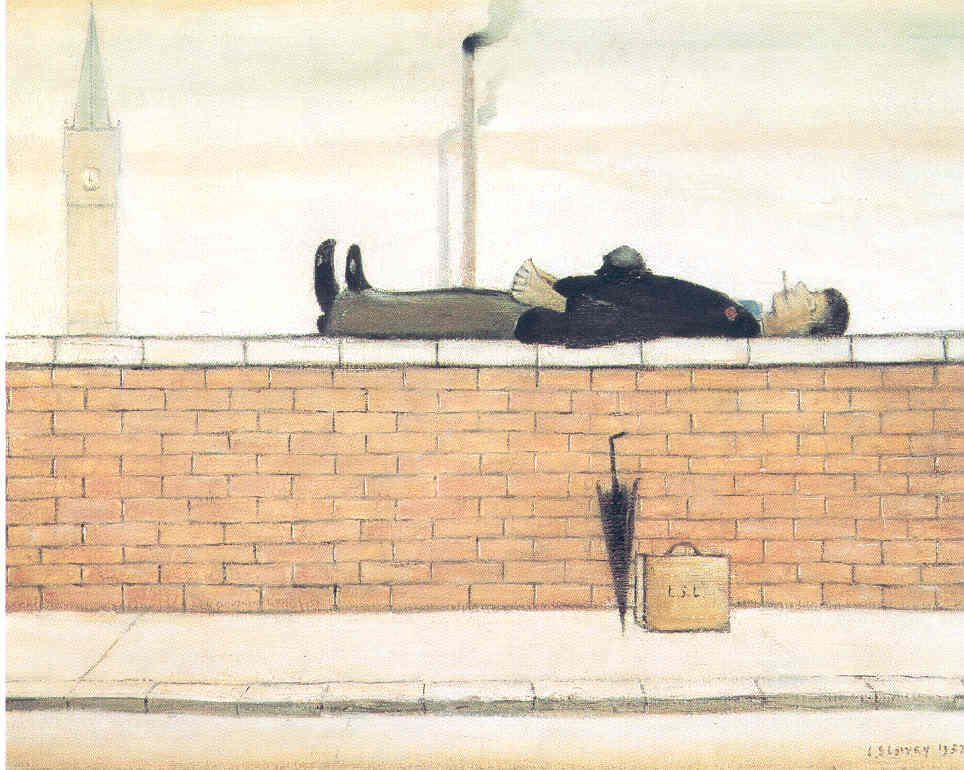

When Lowry’s father died, both he and his mother were saddled with debts which had accumulated from the family striving to live beyond their means in the middle-class area of Victoria Park. When the family’s aspirations come crashing down, Elizabeth becomes embittered and angered at now living within ear-shot of the cotton mills and industrial chimneys that feature in so many of Lowry’s paintings. While she feels demeaned to find herself alongside the working classes, Lowry embraces his situation. Where she sees bleakness, he sees beauty and acceptance. And while on the outside Lowry would seem to have much to complain about, his demeaner maintains a hope, humour and playfulness that comes out in his interactions with the kids, playing street games as he goes about his rent collecting rounds.

This playfulness comes across too in Lowry’s paintings, which early reviewers derided as childish – a criticism with which, in the film, his appearance-conscious mother is only too quick to agree.

“You could be lulled into thinking he was an innocent, but there is a mass of sophistication in his work,” says Spall. “The more I look at him and the more I think about him I realise that he is a brilliant, brilliant artist. There’s nobody like him. He’s imitating nobody and nobody can really imitate him. He’s completely and absolutely, totally and utterly unique. And this thing about him painting like a child. When you go and look at his early work in this gallery here, he was a draftsman, this was a development. He wasn’t a naïve, he wasn’t a primitive. Picasso said: ‘It took me 70 years to learn how to paint like a child.’ That’s Picasso – no-one actually says we’ve got our own Picasso, it’s staring you in the face – he’s called Laurence Lowry”.

No doubt the film will bring a new insight into Lowry’s work. “I had respect but not enough respect,” says Ms Redgrave. “One of the wonderful things about working in this profession is that you get a chance to escape your own ignorance.”

Sadly, Lowry received little recognition during his mother’s lifetime. We can only imagine how probably even more so than her son, Elizabeth would have delighted in learning of the arts centre and five-star hotel in Salford that now bear his name. Perhaps that is why Lowry found such beauty in authentic acceptance, because his mother never had the confidence to enjoy anything someone had not previously deemed beautiful or worthy of attention. In the film’s story at least, Elizabeth is portrayed as a women who feels shame about where the post-war depression has brought her, and her son, for all his hard-work and talent, lived most of his life in the shadow of that shame.

For those who want to learn more about the making of the film, The Lowry is hosting a special display alongside its permanent Lowry exhibition, which includes behind the scenes photographs, props from the set, film clips, mood boards, shooting schedules and the final screenplay signed by the film’s stars.

The exhibition is also a chance to view a selection of paintings and watercolours by Timothy Spall, which he painted during and after filming as L.S. Lowry.

“God knows what people will make of them but they’re out there for people to say what they like,” Spall laughs because as an artist of any kind he knows only too well. “You stick your neck out, you’re going to get it chopped every now and then”.

Mrs Lowry & Son opens nationwide on Friday 30 August 2019. The Mrs Lowry & Son display at The Lowry Galleries, Salford Quays sits alongside The Lowry’s permanent exhibition, LS Lowry: The Art & The Artist.

County Durham centenary celebrations for mining artist Norman Cornish.