In 1991, the artist, Cornelia Parker enlisted the help of the British army to blow up a garden shed. She and her team then collected the scorched and twisted fragments of the shed and its contents (purposefully curated to echo the horticultural and personal bric-a-brac of an average garden shed), painstakingly arranged and suspended them from wires, lit them from a single source, and installed them at the Tate gallery.

This remarkable piece (and my description cannot do it justice) Parker entitled, “Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View.” Eventually, it went on tour, including a four month stay at Manchester’s Whitworth gallery.

The connection between Parker’s masterpiece and Phoebe Eclair-Powell’s Bruntwood prize winner is not made explicit in the production (it doesn’t need to be in the script, but I think a programme note might help those audience members unaware of Parker’s creation).

The set is simple. A flooring of grey, concentric circles which will revolve, mid-action, sometimes clockwise, sometimes anticlockwise; sometimes characters will share the same circle and travel, maintaining proximity or distance, through their dialogue. Other times, they will stand on separate circles, orbiting and passing as they speak. Connection/disconnection.

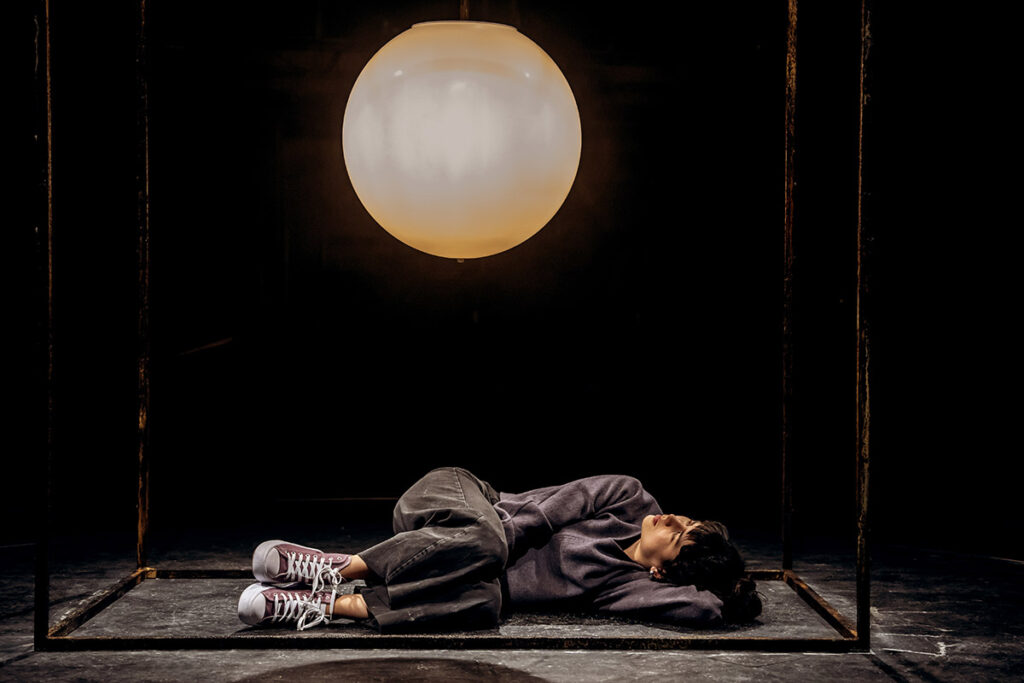

At lights up, a stylised garden shed takes centre stage. This is soon dismantled (rather than exploded), leaving only the basic metal frame and a young woman, in foetal position, on its floor.

The action follows three heterosexual couples, each from a different generation. The youngest are Abi (Norah Lopez Holden) and Mark (Michael Workéyè ). Next up are Naomi (Lizzy Watts) and Frank (Jason Hughes) – Abi’s parents. The elders are Lil (Hayley Carmichael) and Tony (Wil Johnson) – he is on his third marriage, she has been married at least once before. These last two are not related to the others, but connected in significant ways by experience and synchronicity.

Fragmentation informs the structure of the play, as we leap swiftly to and fro over the 31-year time span of the plot (1993-2024). Initially this makes it difficult to gain a sense of these six as people and hence to have any emotional connection with the characters. This becomes less of a problem as the story proceeds and the drama heightens (i.e. it is no problem at all, provided you stick with it and pay close attention early on).

The play runs at about 100 minutes (no interval) and for almost half that it seems like a mildly engaging account of three not particularly unusual couples. There is some humour, a little passion, a modicum of trauma – much what might be expected in any middle class, First World life.

But the piece eventually takes on layers and becomes darker, and we begin to see three women each dealing in her own way with a normalised masculine aggression: wives who become the outlet for a husband’s rage, simply because they are there.

And then there is the sense of responsibility, of guilt, of women who carry a burden of feeling they should have done more. Lil tells us how her first husband, having been violent towards her, went on to murder his next partner. By coincidence, Lil is a guest at the honeymoon hotel chosen by each of the other couples. She has one piece of advice, first for Naomi, later for her daughter, Abi: “Run!”

There are some powerful monologues – Tony battling with dementia is lifted to heartbreaking veracity by Johnson’s physicality – and some moving and funny interchanges between mother and daughter (Watts and Lopez Holden) – watch out for their Britney Spears routine (though, of course, the choice of song is double-edged). Atri Banerjee’s direction is active and at pains to engage with an agitated narrative.

There is the suggestion that women tend to internalise their own anger; Naomi deliberately stepping on broken glass, Abi battling with an eating disorder. They accept violence, they take responsibility for things that are not within their control and, capable as they otherwise are, there is a sense of inevitably, of a lack of options. The men (even Tony, whose illness makes him also a victim) do not come out of this well.

In Wallace Shawn’s convention-breaking play, “My Dinner with André,” theatre director André asks what theatre is for if an audience goes away from a production believing the world is just as bad as they feared it was when they came in? Perhaps Eclair-Powell’s answer would be that a mirror needs to be held in place for as long as it takes for society to accept and act upon what it is being shown.

At the finale, we learn that Naomi is erecting a self-assembly shed and filling it with personal memorabilia with the intention of blowing it up. The Tate’s account of “Cold Dark Matter” seems apt:

“By blowing it up, she is taking away the safe place where a personal history of objects no longer in use – but not quite finished with – is stored. But she is also, in the process of creating an ‘exploded view’, perhaps creating a new space.”

“Shed: Exploded View” is a darkly challenging new work, offering no answers but prompting serious reflection on an enduring and shameful social epidemic.

Shed: Exploded View is at The Royal Exchange, Manchester from 9 February to 2 March 2024. Age guidance14+