Director William Friedkin is often portrayed as an erratic genius. He’s made some amazing films (The French Connection, To Live and Die in LA) and some outright turkeys (Jade, The Guardian). But the film which most people associate with his name is 1973’s The Exorcist, based on a novel by William Peter Blatty, and partly inspired by a true, 1949 case of demonic possession in St Louis. The Catholic Church banned the Priests involved in this particular exorcism from talking about the incident but Blatty unearthed enough details to write a best-seller.

Friedkin’s devotion to realism – bordering on bullying – made it a gruelling shoot: he is reported to have fired a loaded gun into the air to unnerve the actors. During one scene, Ellen Burstyn was pulled across the room on a wire rig with enough force to cause a lifelong back condition. Mercedes McCambridge was cast as the voice of the demon; she ate raw eggs, chain smoked and drank copious amounts of whisky to give her voice a sufficiently rasping quality but was heartbroken when Friedkin – aiming to preserve a sense of mystery – denied her a screen credit.

When the film opened, it was a monster success, with queues around the block. People threw up and passed out; one woman was so terrified she miscarried. Horror had crossed over into the mainstream; this was less a movie, and more a cultural event. Sales of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells (featured during a key scene) went through the roof. Even if you’ve never seen the film, you’ll be aware of the iconic poster image; Father Merrin, illuminated by a bedroom window, standing outside the house of the possessed girl Regan. Over forty five years later, The Exorcist remains the most successful horror film of all time. Given the film’s modern classic status, it’s a brave or foolish soul who would attempt a stage version.

This is only the second production from the Classic Screen To Stage Company but producer Bill Kenwright has been in the game a long time, and clearly knows where to find the best people. Playwright John Pielmeier has chosen to work from Blatty’s novel rather than Friedkin’s film, and there are subtle differences; his measured adaptation works well, allowing more space for Father Karras’ spiritual crisis, which mirrors Regan’s possession. There’s a sense that as Karras’ faith in God weakens, the demon inside Regan grows stronger.

Sean Matthias is an experienced director, as well as an award winning writer and one-time film maker (Bent, about the Nazi persecution of homosexuals). He has an instinctive understanding of this story; horror is as much about what is imagined as what is witnessed. The sound design is a vital part of The Exorcist, and Adam Cork does exemplary work, creating a collage of layered voices, screams, door slams, and scratches to disorientating effect; there’s also a sound like cracking foundations, as if the pillars of civilisation are being ground into rubble.

Designer Anne Fleischle has created a simple set of three rooms and an entrance hall (there are no lumbering scene changes): The exaggerated perspective creates a sense of unease, before the demon arrives. The back wall projections of Jon Driscoll – with animations from Gemma Carrington – feature images of shadows, scuttling rats, and flames, and add another layer of terror to the proceedings.

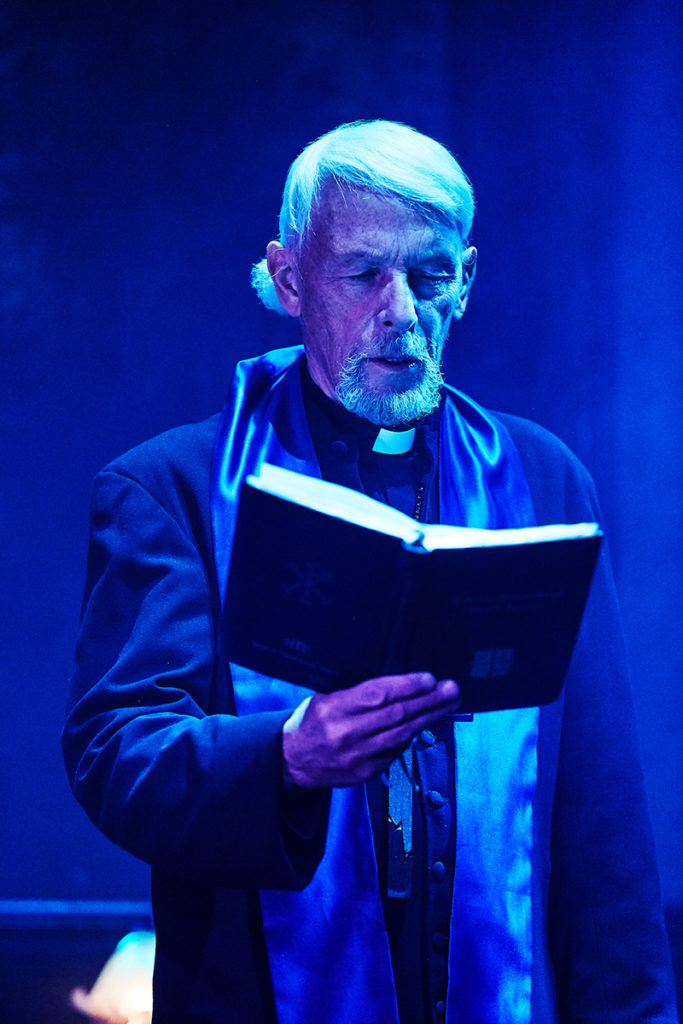

I will always have time for singer/actor Paul Nicholas, thanks to his cheerily malevolent turn as Cousin Kevin in the film Tommy, though to most people, he is still Vince Pinner in sit-com Just Good Friends. He receives top-billing in The Exorcist but as Merrin, his contribution is basically a last act cameo, and he’s not required to do more than wave a crucifix and recite some Latin. The core of the drama is the dynamic between Karras, Regan and her mother, Chris MacNeill: Sophie Ward brings the right amount of concern and bewilderment to the latter, and her encounters with Karras have an ambiguous spark.

Karras chose to follow God, and by doing so, accepted a life of penury. He is tormented by the fact he didn’t have sufficient resources to provide his late mother with a better degree of care. Ben Caplan is very good in the role, often switching between victimhood and heroism in the same scene, and his final sacrifice is quietly shattering. Is there a happy ending? For some yes, for others not.

Ultimately, it’s Regan who sits at the centre of this world-in-meltdown, and Susannah Edgely is never-less than fantastic. Regan is an innocent, and her corruption gives this production its discomforting power. Edgely’s body language becomes increasingly flamboyant during the possession scenes, as if the demon has taken up permanent residence.

And there’s the bonus casting of Ian McKellen as the mellifluous and sneering voice of the demon (the actor has worked with Matthias on numerous occasions). Changing the sex of the demon from female to male is a major artistic decision that alters the sub text. In their early encounters, there’s a definite sense the demon is grooming Regan, encouraging her to indulge in transgressive behaviours that will satisfy his dark appetite; these scenes lay the groundwork for Regan’s later, sexual acting out. Yes, The Exorcist is a story about the occult but in 2019, it’s impossible not to view material like this and think about the pervasive wound of child abuse which exists, seemingly across all strata of modern society.

There are warnings on the poster. It’s a roller coaster ride and certainly not for the faint-hearted (on opening night, several people left at the interval). But the public has always had an appetite for stage horror; ghost story The Woman in Black has been running in the West End for 28 years. There’s no reason why The Exorcist shouldn’t enjoy the same level of longevity.

★ ★ ★ ★The Exorcist is at The Opera House, Manchester from 22-26 October 2019.