Lorraine Worsley-Carter stumbles upon a unique wonder of the canal age in Salford

After taking a short cut to our favourite Trafford DIY store, our sat-nav suggested a route which took us over an old bridge which we had not traversed before. Glancing through the passenger window, I spied what I thought was an old swing bridge, and we stopped to explore.

At first, we were concerned that we couldn’t find a suitable parking spot, however, if you drive over the bridge towards Trafford, on the immediate right we found Barton Old Road. There we found parking and benches. It really is worth exploring the immediate area by foot if possible.

Once again, a piece of our industrial history was before us, namely Barton Swing Bridge which replaced Barton Aqueduct in 1894.

In its day Barton Aqueduct was hailed as ‘one of the seven wonders of the canal age’ and an amazing feat of engineering for its time.

In 1859, the 3rd Duke of Bridgewater wanted to take the Bridgewater Canal into Manchester, over the River Irwell, in order to expand the canal system and transport the coal from the mines that he owned in Worsley. On the recommendation of his estate manager, John Gilbert, for the Duke consulted Engineer, James Brindley and he suggested the revolutionary idea of bridging the Irwell by a stone aqueduct sealed tight with puddle clay. Obviously, Brindley was a man with ideas ahead of his time and it seems he had little formal education. He must have been quite a visionary as little of his designs were committed to drawings!

Water in the Swing Bridge

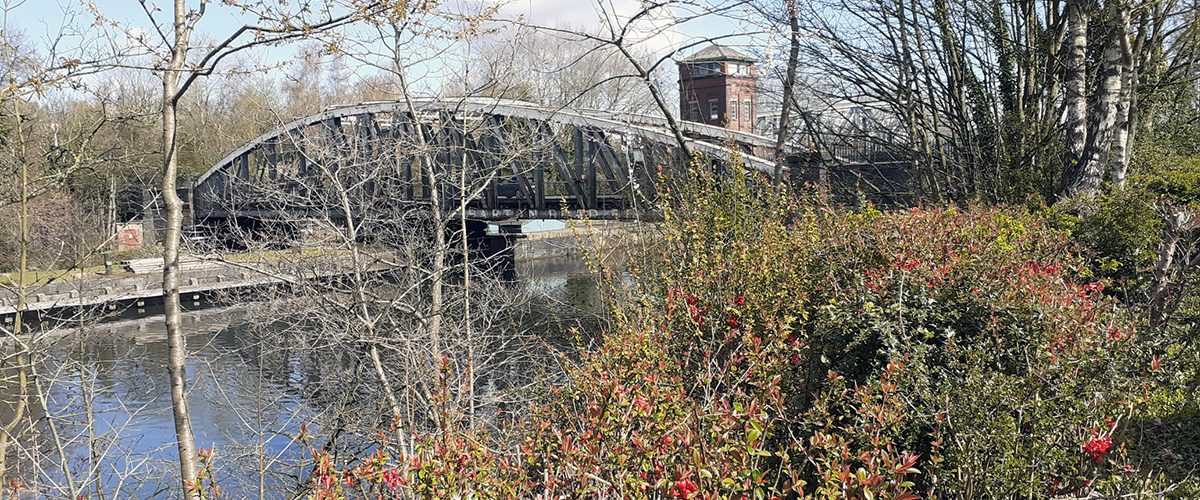

View of Swing Bridge over the Manchester Ship Canal leading into Manchester

There are steps available to see the water in the swing bridge

Operational building for Swing Bridge

Barton Swing Aqueduct: Old operational mechanisms for the swing bridge

When questioned by the parliamentary committee about the composition of the ‘puddle’ that he frequently referred to in his evidence, he demonstrated by having a mass of clay brought into the committee room. He formed the clay into a trough and showed how it would only form a watertight seal, if it had been worked with water to form a puddle.

Fellow engineers scoffed at his idea and one is reported to have commented: “I have often heard of castles in the air but have never seen before where one was to be erected.” Parliamentary permission was required to alter the route of the canal and when, through lack of any drawings, Parliament could not understand what his design would look like, he brought in a huge round of cheese, cut it in half, and laid an object on top of it to demonstrate the principle of his aqueduct. The Act of Parliament was passed in 1760 and work began.

At about 200 yards (180 m) long, 12 yards (11 m) wide and 39 feet (12 m) above the river at its highest point, the aqueduct was, for its time, an enormous construction. Construction proceeded quickly, but disaster almost struck on the day that the aqueduct was first filled with water when one of its three arches began to buckle under the weight.

Brindley, overcome with anxiety, retired to his bed at the Bishop Blaize tavern in nearby Stretford; a Wetherspoons Pub/Restaurant stands on the spot today.

The day was saved when John Gilbert, realised that Brindley had placed too much weight on the sides of the arch, so had the clay removed and laid layers of straw and freshly puddled clay; when the water was allowed to flow in again the masonry held steady and firm.

Remedial work took several months, but on the 17 July 1761, the aqueduct was opened to traffic only 15 months after the passing of the Act of Parliament enabling the work to begin.

Barton Aqueduct’s fate was sealed with the passage of the Manchester Ship Canal Act 1885, which allowed for the construction of a navigable waterway large enough to accommodate ocean-going vessels from the estuary of the River Mersey into Manchester a stretch of 36 miles (58 km) and partly along the Irwell. The arches of the aqueduct were too small to allow large ships to pass through and so it was demolished in 1893. The old aqueduct was so strong and solid that dynamite had to be used to expedite its demolition.

Some of the stonework of Brindley’s aqueduct has been preserved in the nearby Barton Memorial Arch, a monument to his ‘castle in the air’. It’s difficult to find at first. However, if you stand at the crossroads of Barton Road and Barton Lane with your back to the swing bridge information board you will see it on the opposite side of the road, there is a red plaque and you can just make out the wording on the original memorial stone.

John Gilbert went on to work on many canal projects with both the Duke and James Brindley, including the Trent and Mersey Canal.

The Barton Swing Aqueduct that we see, still working today, opened in 1894. It carries the Bridgewater Canal across the Manchester Ship Canal. The swinging action allows large vessels using the ship canal to pass through and smaller craft, both broad-beam barges and narrow boats to cross over the top.

Designed by Sir Edward Leader Williams and built by Andrew Handyside and Co of Derby (who also made our familiar red post boxes), it is considered a major feat of Victorian civil engineering.

So, what I thought was ‘an old swing bridge’, the Barton Swing Aqueduct, is a Grade II listed building. It is still a working aqueduct and the first and only example of its type in the world.