In 1817 bookseller, publisher and satirist William Hone stood trial for parodying religion, the despotic government and the libidinous monarchy. His only real crime was to be funny.

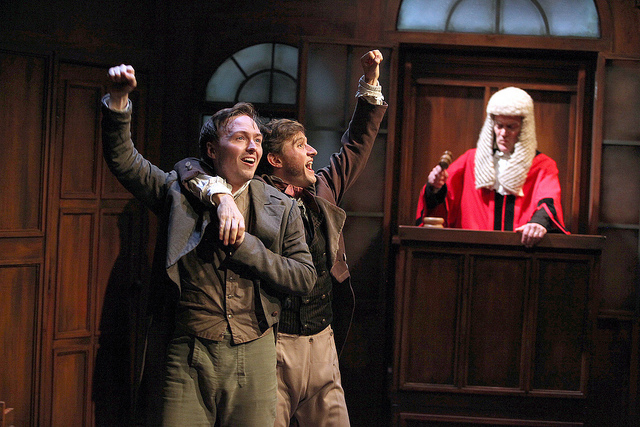

Just over 200 years later, this forgotten hero of free speech, and likely first investigative journalist, is centre stage again in a new play by satirists Ian Hislop and Nick Newman, Trial By Laughter.

Quays Life meets the writers to find out more.

How would you sum up the premise of Trial By Laughter?

Nick: It’s a story about press freedom and free speech and a battle for freedom and free speech. It’s the story of a trial in 1817 – the trial of a man called William Hone, who was a sort of shy bookseller and publisher of cartoons and satirical pamphlets. He was taken to court by the Regency government to try and stifle jokes about the monarchy. That’s essentially what it’s about.

Ian: It’s exactly that. It’s a courtroom thriller but it’s a historical courtroom thriller with jokes, which means it’s three different genres in one for just one ticket price.

Nick: I think we’d describe it as The Madness Of King George meets A Few Good Men…

Ian: Meets Crown Court.

What was the original inspiration for the radio play?

Nick: We’d just finished doing The Wipers Times for BBC2, when we did the film of it, and the head of BBC2, Janice Hadlow sent us an email asking if we’d heard of William Hone. Janice is an expert on Regency history and has written books about it. We both said ‘Who?’ which is often a very good starting point for a story because we think ‘Well, if we don’t know anything about it let’s find out’. We started doing research and suddenly out came this amazing story about this amazing man – a complete nobody really but who took on the might of the government in a landmark case.

Ian: It’s incredible. He had his moment when history beckoned and then fell into obscurity, to our shame really. I’m the editor of Private Eye and Nick’s a cartoonist yet we didn’t know about him, but again that makes for a much better story because you’re telling people something new.

From researching the tale what were you most surprised or interested to learn about Hone?

Ian: Without giving spoilers, it’s incredible that they tried him three times in three days. At the end of each day when the jury found him innocent they just tried him again the next morning until there were 20,000 people outside the Guildhall and they thought ‘We’re going to have a riot now’. This was only a couple of decades after the French Revolution.

Nick: And a year before the Peterloo Massacre so tensions were incredibly high. The Crown was very worried about the possibility of revolution and there were failed harvests and a lot of famine, squalor and whatnot. Meanwhile the Prince Regent was being portrayed in cartoons and in pamphlets as this libertine voluptuary who was scoffing vast quantities of food while people were hanging outside the windows. The other thing we discovered about Hone as we did more research is what a remarkable man he was because he wasn’t just a satirist, which was our first interest and his friendship with the cartoonist Cruikshank interested me as a cartoonist myself. Their working relationship was also a natural thing for us to explore and Hone was also probably our first investigative journalist. He was a witness to the execution of a young serving girl, a maid called Eliza Fenning, and he was absolutely appalled by it. He did a lot of research into her case and basically proved that it was a miscarriage of justice. We also learned he was an amazing philanthropist and he took a terrific interest in the lunatic asylums and campaigned for better conditions. There was the reform of juries, which he campaigned for and won. He never stopped working.

Ian: And he believed in universal suffrage, which at the time was a good 100 years away. If you look at his range of interests, they are pretty extraordinary.

What changes have you made in preparing the play for the stage?

Ian: It’s completely different. The thing about radio is that it has to be very words-driven, which is fine because there are lots of bits about speeches and whatever, but to get it to the stage we have to make it more dramatic. There’s a lot more about the role of his wife and we’ve set more of it in pubs.

Nick: It’s a matter of fact that Hone and Cruikshank devised their strategy for the case in all the pubs and coffee houses of London so it’s a very rich milieu in which they were working. Hone was admired at the time by his literary colleagues, even though he was always bankrupt and had schemes which lost him money, and one of his admirers was William Hazlitt, who was one of the most caustic critics of the era. The only person Hazlitt seemed to like was William Hone so we’ve put Hazlitt in the story as well, which is great for the colour.

What do you feel makes Hone’s story a great subject for a play?

Ian: Hone’s tactic in the trial was to appeal to the jury so his whole way of winning was to make it accessible to an ordinary… I’d hate to say viewer but that’s sort of how he approached it. Courtrooms are great theatre on the whole and Hone and Cruikshank, in devising the strategy as it were, realised that playing to the gallery is not a bad thing in a big trial – it’s what you need to do because you need to get them on your side. That’s exactly what happens in the theatre.

Nick: What was slightly unusual about their tactics is that they set out to make the jury laugh. The basic of their entire case was that Hone spoke for six-to-eight hours every day of the trials just producing more and more examples of stuff he thought would make people laugh – and they did. There are some transcripts, which admittedly were edited or written by Hone so he did beef up his own amusingness quite a lot.

Ian: A bit like Oscar Wilde writing the account of his own trial and Hone’s account is fantastic. He’s brilliant in it, unsurprisingly because he edited it.

Nick: History written by the victors…

Ian: Yes and it’s bloody funny.

How you feel the subject matter resonates for contemporary audiences?

Ian: I think it’s a reminder that this battle has to be won in every generation. We are incredibly privileged to be the beneficiaries of all those battles that were won in Britain in the 19th century but they can be lost again. History doesn’t only go one way.

Nick: And the arguments that are buzzing around now are very similar. Hone was targeted because he wrote parodies of religious text, principally The Lord’s Prayer and the Litany and The Ten Commandments, and they were the sort of stuff we’d put in Private Eye now for a bit of fun. Only the other week you had Rowan Atkinson talking about ‘Should we be allowed to make jokes about religion?’ Hone believed you should if the context is political or whatever and that’s what free speech is. On a global scale there are cartoonists in Turkey and Malaysia who are still being persecuted and there’s this amazing Malaysian cartoonist called Zunar who until recently faced 45 years in jail for seditious libel, which is basically the same charge that was levied against Hone, for making jokes about the Prime Minister and his wife. Zunar, like Hone, could have done a runner. I met him when he was over in England but he was going back to face trial because he felt this was an important case, like Hone did, that establishes what we can and can’t say about our rulers.

You’ve worked with director Caroline Leslie a few times now. What do you enjoy about the collaboration?

Ian: [Laughs] She’s very annoying because she demands you put in new scenes and change things around to try and make it better.

Nick: What’s that joke? ‘How many writers does it take to change a lightbulb?’

Ian: ‘None – don’t change anything!’

Nick: That’s very much our view but Caroline forces her to make changes. We first started working with her on our first play we did, A Bunch Of Amateurs, and she was absolutely brilliant and brought all kinds of things to the script which we didn’t know were there, including a lot of music. Then she directed The Wipers Times and that’s a play that’s full of music and movement and we wrote it accordingly because we thought ‘Caroline’s very good at this so let’s make sure she has a lot of stuff to work with’.

Ian: It’s very good having a woman director, particularly in situations that are quite blokey by definition like the Army and English court in the 1800s. She makes sure that it expands beyond that and that the emotional elements are not ignored.

This is your third play to be developed by the Watermill Theatre. What do you see as its importance to the UK theatre scene?

Ian: It’s a very exciting place to work.

Nick: It’s a remarkable theatre. Apart from being a jewel in terms of its setting and the closeness to the stage you have as an audience, the standard of productions has been incredible. I first came across it when they did a production of Sweeney Todd in 2004 which transferred to the West End. They’re just brilliant at doing things, particularly with music. When we were invited to do A Bunch Of Amateurs there we knew nothing about the Watermill but we enjoyed the experience so much that if we were able to we’d always go there because the audiences are lovely and it’s a great place to do a play.

You’ve been writing together for a long time. How would you describe your collaborative process?

Ian: We write together, literally. We don’t send each other drafts and we physically work together in the same room. I suppose we try and make each other laugh; that’s the first thing. But we’ve known each other long enough to be able to say ‘That isn’t very good’ or ‘That’s a terrible suggestion’ and then just get on with it. There’s a sort of joint self-editing.

Nick: There’s always a lot of energy when it’s the two of us doing something, particularly because Ian’s time is so precious because he’s everywhere. When we get together we have to get on and do some writing. We tend to work quite fast. We both do stuff independently but to edit each other as we go is a sort of bonus. I’ve got lots of writer friends who write on their own, which I think is a very ghastly prospect. They have to rewrite and rewrite and rewrite; if you look at the greats like Alan Bennett, his diaries are full of the pain of rewriting. We have to rewrite as well but it’s a bit less than if we working on our own.

Ian: Because Nick’s a cartoonist he’s always had a strong visual sense whereas I tend to be a bit more word-bound. So there’s always a point where Nick’s thinking ‘What would look great is this…’ which I usually haven’t thought of. I’m thinking ‘This bit I’ve just written would be really clever’ when actually if might be terribly boring and getting something across visually is what it’s all about. That’s another reason we really enjoy collaborating.

How hands-on are you with your touring productions?

Nick: They take on a life of their own really. If we go do a Q&A we see the show and occasionally have some notes, which we pass on to our producer or to Caroline. But really by opening night it’s all pretty much there.

Ian: [Laughs] Our notes are always ‘Could the actors not ad-lib please? Can they only say exactly what we’ve written?’.

You are doing post-show Q&As again for Trial By Laughter. What do like about the process?

Nick: The ones we have done for The Wipers Times are always very instructive because we meet people who’ve got their own stories to tell. We did a Q&A down in Chichester last year and a lady in the front row said ‘I have a little knowledge of this subject because my grandfather was Fred Roberts [who edited the paper]’ so we said ‘Please come up on stage’ and we just sat there asking her questions about him. It’s a great way of interacting with your audience. In Salisbury we were talking about trying to make The First World War accessible to younger audiences through a humorous story and a young girl at the back who was around 13 went ‘Well, it works!’ With the Q&As you get a bit of a discussion going and a bit of a debate.

Ian: There was a great moment just before one of the Q&As where someone said ‘There’s an Army chap in the audience who said he thought you’d got it pretty much right’ and when we asked who he was they said he was Deputy Supreme Commander Allied Nato Forces.

What you hope to get out of the Trial By Laughter Q&As?

Ian: We want to know what they think really, what bits they’re interested in and whether they think we should still be worried about this sort of thing. Hopefully they’ll think we very much should be.

Nick: We’ve become very energised by this subject matter and we’ve found it fascinating. All we’re really trying to do is try and get other people as interested in it as we are. We happen to think Hone is one of the most brilliant men in history and we hope other people share our opinion

The Wipers Times is touring the UK before heading into the West End and Trial By Laughter is heading out on tour. Is this your bid for theatrical domination?

Ian: [Laughs] Everyone else is toast. No, we’ve come to theatre a bit late I suppose in terms of writing. We’ve done a lot more telly and some film, but it is fabulous and there’s nothing like it – the pleasure of crafting something that goes on to have a life of its own, where it plays in different places and has different reactions from an audience. It’s incredibly rewarding.

Nick: It’s one of the biggest surprises of our writing career that this has happened. Never in our wildest dreams would we have thought of doing a play but then we were asked to. Now we can’t think of anything we’d rather do. We wrote the original radio script of Trial By Laughter with an eye to thinking ‘This has theatrical legs’.

Trial by Laughter is at The Lowry, Salford Quays from 29 January to 2 February 2019.